Written by Craig Kerslake (Wiradjuri architect and Managing Director, Nguluway DesignInc) and Lynne Hancock (Principal, DesignInc Sydney).

Have we over-valued privacy to the detriment of social interaction and a sense of community? Indigenous thinking would suggest we have.

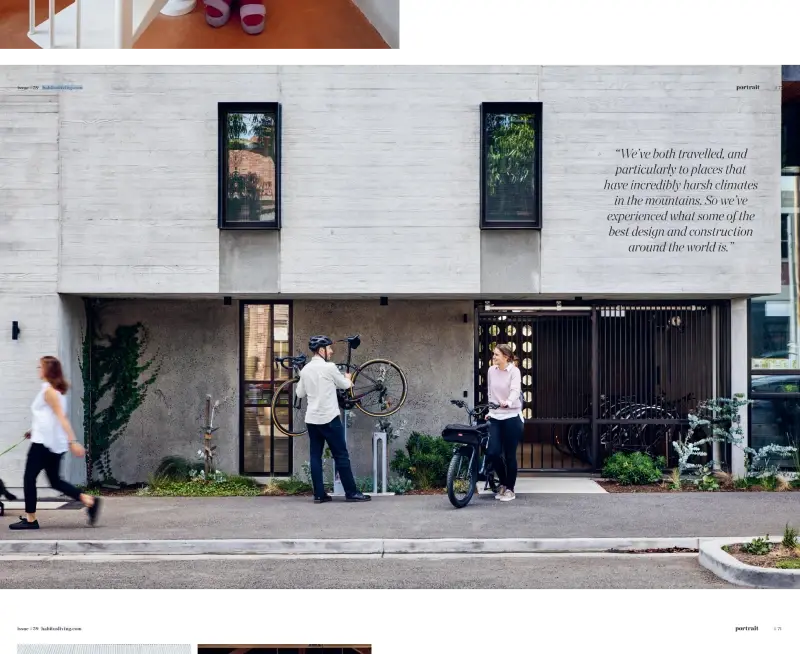

Nguluway DesignInc has developed a Designing from Country approach that values and encourages the incidental social sparks – sparks that happen where living spaces are directly connected to circulation spaces; where front doors are also open doors; where home is the whole building and not just the individual apartment. This applies to a range of typologies, from medium-density apartments and seniors living to communal and co-living.

The fundamental approach is predicated on reprioritising ‘connection’ as opposed to personal freedom – connecting us first to nature, and then to each other. While private spaces have a place, the obsession with privacy at all costs is challenged.

Brackish space at all scales

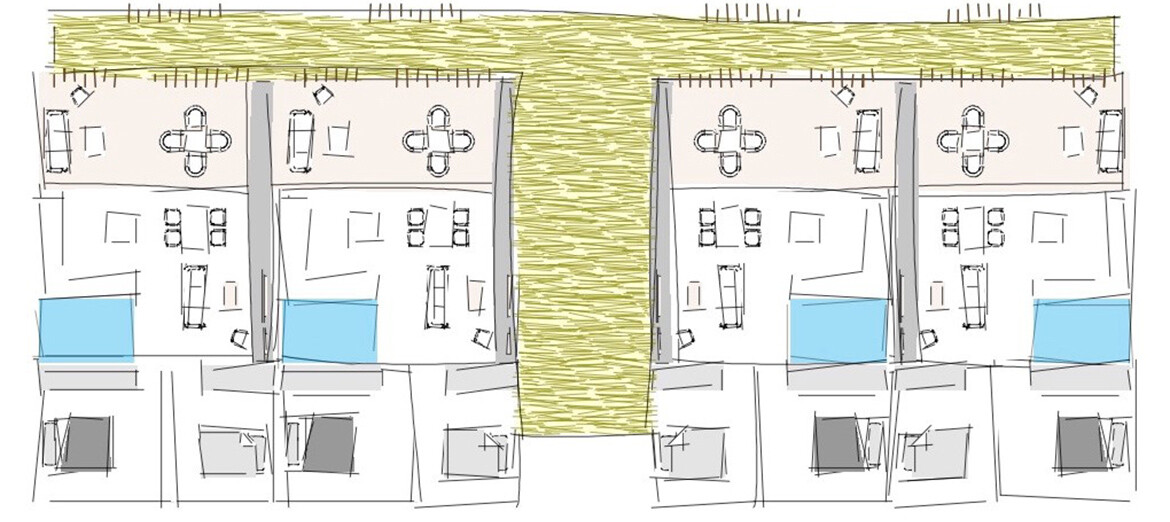

Aunty’s House is a medium-density housing concept that uses the broad definition of ‘family’ in Aboriginal communities to rethink spatial planning. The plan stacks apartments above each other, with circulation via a pedestrian path along the front of each level. While at first glance this has something in common with the ‘street in the sky’ typology that has come to define 1960s social housing, there is a significant and conscious difference: the layering of spatial zones to facilitate connection and care across multiple households.

An intermediate area between the public and private creates what in Aboriginal terms could be called a ‘brackish space’ – a place for mingling rather than separating. From the entry path, each apartment has a generous verandah or porch that leads directly to the living rooms, with private bedrooms behind. This flips the traditional Western layout, where the rooms immediately off the walkway are more defensive than they are inviting: utilities, kitchen, sometimes a bedroom; and the living spaces and balcony are treated as fully private areas, out of the reach of public circulation.

When we design in brackish spaces at the outset, it resets our priorities. It requires that we wrap other architectural spatial considerations around the primacy of the threshold in-between space – the space where we come together.

Related: Meet Susan Moylan-Coombs

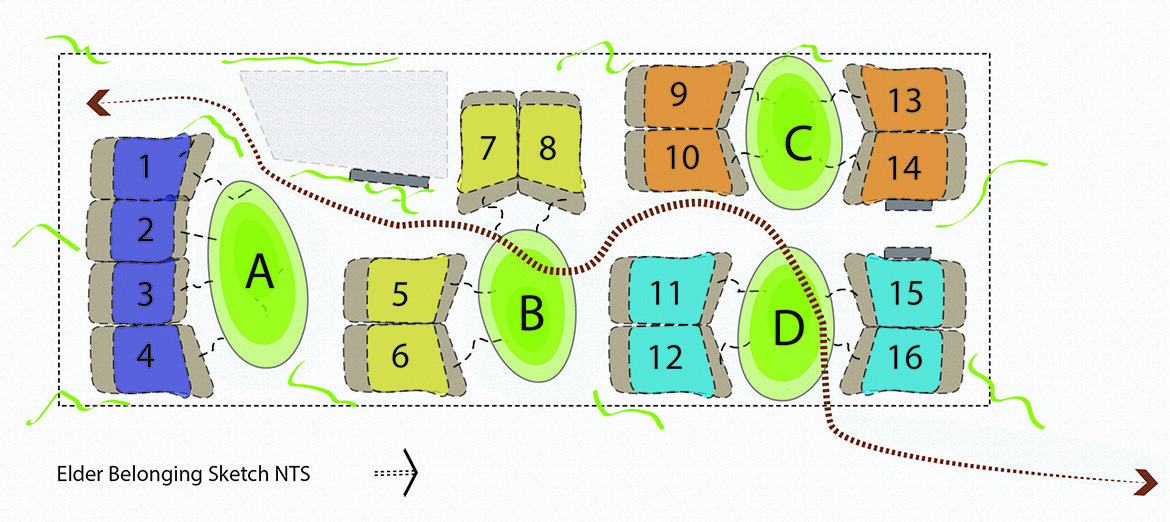

We must also consider the needs of Elders to age in place, in community and connected to Country. In the Aboriginal Seniors Housing Spatial Planning Concept masterplan, engagement with local Tharawal Elders informed a design for clusters of dwellings – all accessible, all connected by communal outdoor spaces, and all within a landscape setting combining endemic plants species, softscape pathways, places to sit and yarn.

The outdoor spaces and verandahs optimise opportunities for interaction, while privacy is maximised in the sleeping areas. The masterplan process began without buildings, producing a sketch that simply placed four neighbourhoods on the site in a non-traditional approach that was nevertheless embraced by the client.

Further afield, we produced an alternative housing design reflective of and suitable for the Anangu people in Central Australia. Designing from Country at every step, the planning considers social dynamics such as extended family arrangements and specific gender spaces, protocols around separate spaces, and connecting built form to ‘Grandmother earth.’ Layering spaces around the cultural idea of journey, an experiential hierarchy was established from the public point of arrival into more private, introspective spaces. Flexible sleeping and living options are now viable for guests, with seats that can transform into sleepout beds and allow people to take advantage of the cool breezes.

These pilot projects bring First Nations cultural values and kinship structures to medium-density housing, seniors housing and co-living typologies. The approach could equally well be applied to individual dwellings. Whether apartments or houses, the benefits to residents and their surrounds lie in fostering connections, creating a sense of belonging and building community.

Designing from Country, the Housing SEPP and affordability

How is Designing from Country relevant to the Housing SEPP (State Environmental Planning Policy), and to affordable housing and housing generally?

With growing populations, and housing stress evident across Australia’s towns and cities, the very notion of a ‘slow time’ approach to understanding and responding to place seems to contradict the need for speed of supply. Doesn’t Designing from Country just get in the way of efficiency and risk clogging up the pipeline?

The reforms in the new Housing SEPP aim to boost supply and delivery of affordable housing for the benefit of lower- and moderate-income households. For developers, this spells plenty of benefits. Increasing the development potential of sites through height and floor space ratio (FSR) bonuses effectively increases the value of that site; put crudely, you can get more ‘bang for your buck.’ While an incentive, it is also a risk if the benefits are not passed on to residents.

We believe that it is possible to do both: that, as well as achieving more homes, there is also an opportunity to design them better. From our perspective, this is an ethical imperative.

Rethinking how we live together in our community opens up new possibilities for housing design.

Think about the social impact of shifting the emphasis from larger private spaces towards larger shared spaces. It doesn’t necessarily mean developments need to become more ‘space-hungry’ – rather, a redistribution of spaces within the living environment can serve multiple purposes including functionality, amenity, sustainability and community.

An Indigenous lens on the Housing SEPP means the social requirements of people and the aspirations of developers are met somewhere in brackish space. The outcomes can in fact be more valuable on many levels. When people feel more connected to the natural environment and there are strong social bonds and community, real estate also increases in value. The enduring outcome is better neighbourhoods, social harmony and a sense of identity.

Nguluway Designinc

nguluway.designinc.com.au