What can I tell you about Marc Newson that you don’t already know? I can tell you he was once expelled from high school for dying his hair blue, red and silver. Maybe twice. I can tell you about that time in the late 80s when he drove me to a nightclub in his clunky Citroën DS 19. Backwards, through the darkened streets of Darlinghurst. I can tell you that when I proposed a Newson profile to my editor at The Australian in the early 1990s, she wanted my assurance that he wasn’t just a flash in the pan, another wide-eyed expat who would eventually fizzle into oblivion. He wasn’t and he didn’t, but you knew that already.

For anybody who’s spent the past three decades in a panic room, a recap. Marc Newson is one of the most prolific designers on the planet. He has devised luggage for Vuitton, cookware for Tefal, an aeroplane for the Cartier Foundation in Paris. He’s delivered a recording studio in Tokyo. A restaurant in London, two in New York, all three now defunct. Dish racks for Magis, ovens (Smeg), eyewear (Lanvin), sneakers (Nike), a shotgun for Beretta. An updated Riva speedboat in very limited edition. His 2007 exhibition at New York’s Gagosian Gallery – which made Marc Newson the only industrial designer to figure in the same stable as Marcel Duchamp, Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons – was described by The New York Times as “a new high” in the already frenzied design-art market. If you’re clever you can still spot a one-off Newson door handle on what was once a fashion store on Oxford Street, Paddington, Sydney. Don’t say I sent you.

Marc’s latest creation is his third iteration of the cultish Atmos clock for Swiss timekeeper, Jaeger-LeCoultre. The ultimate in geek chic, an Atmos is a torsion pendulum timepiece which derives its energy from changes in temperature and atmospheric pressure and can run for years without human intervention. It was invented in the early 17th century by a Dutchman by the name of Cornelis Drebbel who also, incidentally, built the world’s first navigable submarine – one of the few forms of motor transportation Marc hasn’t tackled. Watches and clocks he has a’plenty.

“Time,” he sighs. “It’s paradoxical really since I’ve designed so many timepieces, but the thing I would simply love to have more of is time. Not more time to do what I really love doing because in fact I’m already doing that. But today I’m having to do ten times more things in ten times less, um, time!”

In the weeks preceding our conversation, the 53-year-old designer Time magazine once listed among its 100 Most Influential People had been around the world – Milan, Tokyo, San Francisco, New York, Paris, Venice, Madrid and Geneva to be precise. When I finally get ahold of him, he’s just stepped back into his London studio which is housed in a red brick Edwardian building, a repurposed mail-sorting office ten minutes’ walk from Westminster Abby. “I’m back for a few days, which is about as much as I get to stay anywhere these days. It’s kind of non-stop.”

Except, perhaps, when he heads to his home on Ithaca. Home, in the sense that the tiny Ionian Island is where his mother’s family hails from. The cottage in which his grandfather was born is still standing, although said progenitor emigrated to Australia in 1923. His daughter Carol married electrician Paul Newson when she was 19 and pregnant with Marc. Newson père left by the time the infant was two, and Marc’s mother remarried to become Carol Conomos – an old Greek name – when he was twelve.

It was to granddad’s garage in the Sydney suburbs that young Marc Newson would retreat to tinker. By his own admission “a diabolical student”, he was interested in art, “though hardly a virtuoso draftsman”. He was apparently a deft hand with billy carts, anything with wheels. Still is.

His grandfather’s Ithaca cottage is still in the Newson family, though not on Marc’s estate. Not yet anyway. “We’ve had a house on the island since 2010 or so, and I’ve been buying up parcels of land adjacent to my property as they come up. Our house is a little bolt hole really, a teeny thing. We started construction on the big house two years ago.”

Marc’s grandfather, like many of his compatriots, emigrated to Australia after the First World War seeking a new life among folk his fellow Greek émigré, Nino Culotta (aka John O’Grady) would call “A Weird Mob”. Others left for Canada, South Africa or the United States, depleting Ithaca’s population to the point where today it peaks at a little over 3000. “I’ve no family left on the island,” says Marc. “But I do have a strong connection to the place. In summer it’s overrun with people from all the countries their ancestors emigrated to, heading back to their roots. You hear so many Australian accents you could think yourself in Sydney. In some ways it’s quite nice, in other ways it’s kind of weird.”

There’s something compellingly apropos about Marc’s roots being in Ithaca, legendary home of Homer’s Odysseus, the restless warrior we know as Ulysses. In the design world, Marc’s personal odyssey is the stuff of living legend.

Marc Newson was born in Sydney on October 20, 1963. He was raised by his mother, with his maternal grandfather and an uncle, Stephen, as male influences. Partial to working with his hands, in 1981 he enrolled in the jewellery design course at Sydney College of the Arts. Not because he had any intention of forging a career in bijoux but because, as he puts it, “it was the one thing in art school you could do that had a deeply practical nature. Everything else seemed to me so esoteric. If I hadn’t have gone to Sydney College of the Arts I would have been a perfect candidate for an apprenticeship or something.”

Inspired by the work of Ettore Sottsass and the Memphis movement, Marc became intrigued by the expressive essence of furniture. He seduced his tutors into conceding that furniture and jewellery were interchangeable, both existing in relation to the human body. And so his three Graduate Pieces were prototypes for chairs which combined the playful geometries of Memphis with the rugged materiality of High Tech. In doing so, he reconciled the parallel trajectories of, respectively, Post Modernism and Late Modernism. Though I’m not sure that’s what he had in mind.

“It’s important to bear in mind that all my work should not be taken too seriously, but enjoyed (I hope) for its beauty + witt (sic).” This is from a fax hand-written by Newson to Ute Rose, the recently retired general manager of Anibou, dated July 14th, 1989. It concerned his sensuous Wood chair, designed as a commissioned piece for the Crafts Council of New South Wales in 1988.

ST: Do you still think that your work shouldn’t be taken too seriously?

MN: I think so, yes. I think the comment about seriousness still holds for me today. I’ve always felt, philosophically, that one shouldn’t over-intellectualise. At the end of the day what I’m doing is offering a choice. Not in the case of a big luxury yacht, but certainly in the case of a piece of luggage or an appliance, a watch or you name it. It’s not about offering a solution, it’s about offering my opinion, my take on it. That’s one of the things I love about design, you’re not obliged to live with it if you don’t want to.

Marc made his mark as a savvy stylist early on. His graduate pieces were A-framed tubular metal struts supporting rolled aluminum volumes, easy on the eye but hard on the butt. His tripodal Insect chair – the precursor to his iconic Embryo chair – had a tendency to topple. That early Orgone shape, the rounded figure-8, became a de facto trademark, informing the Embryo chair of 1988, the Sine chair (1988), Wicker chair (1990), Felt chair (1993), Gemini pepper grinder (1997), door stopper (2002) as well as a string of things actually called Orgone (Chair, Lounge, Table, Stretch Lounge etc…).

It was also, of course, the foundation of the now infamous Lockheed Lounge of ’88 and the less celebrated Pod of Drawers of the year before. He borrowed the Lockheed shape from the lounge upon which Madame Juliette Récamier reclines in her portrait painted by Jacques-Louis David at the turn of the 19th Century. (So iconic is David’s image that elongated sled seats are today referred to as ‘recamiers’.)

The Pod shape he appropriated from André Groult’s Chiffonier Anthropomorphique (anthropomorphic cupboard) of 1925. It’s interesting to think that a designer most often dubbed a retro-futurist for the Atomic era, sci-fi feel of his work actually drew inspiration from the history of French decorative arts. (Both the David and Groult works are on permanent display at the Louvre, Paris.)

“There was a time Marc was trying to shoehorn that Orgone shape into every single project,” says one design commentator, who wishes to remain nameless. True, it did become a bit predictable for a while there. Marc parries: “That Orgone shape was like a tool that I used at a certain moment in time. A lot of the time it was unconscious, it would just kind of materialise in a design without me really thinking about it. I’ve never characterised my work as ‘organic’, it’s too general a term. But if it ever was, it’s not as organic now as it used to be. These days I’ve moved on to a more rational design.”

ST: Is that a result of the clients and projects you’re working on now, or is it coming from an interior drive?

MN: I think it’s both really. It’s coming from me, and it’s also a response to having to solve problems in a more rational way. In a more pragmatic way. It would be like the tail wagging the dog, to let a single motif like the Orgone shape drive the whole shebang.

Marc’s private clients these days tend to be the stealth wealthy, the nameless oligarchs and other captains of industries unknowable, people who sail and fly and otherwise rotate off the radar of we mere mortals.

ST: So, the yacht your working on for a private client, are they Greek?

MN: Yes. No. They’re Eastern European. No, that’s not correct. What can I say? I’m sworn to secrecy. It’s for a very wealthy private client, that’s about all I can say.

Newson most recently completed a BBJ (as in Boeing Business Jet, which seats between 25 and 50 passengers in a luxury configuration), and is currently working on 14 passenger and six passenger private crafts.

“What a lot of people don’t get about Marc is that he’s actually very hands on,” says Newson’s friend and colleague, Richard Allan. “He’s very much into the way things are made, as much as the way they look. He’s really curious about materials and how they can be used in new ways. He’s probably the most driven person I’ve met in my life, never sits still (except after a number of drinks).” (laughs)

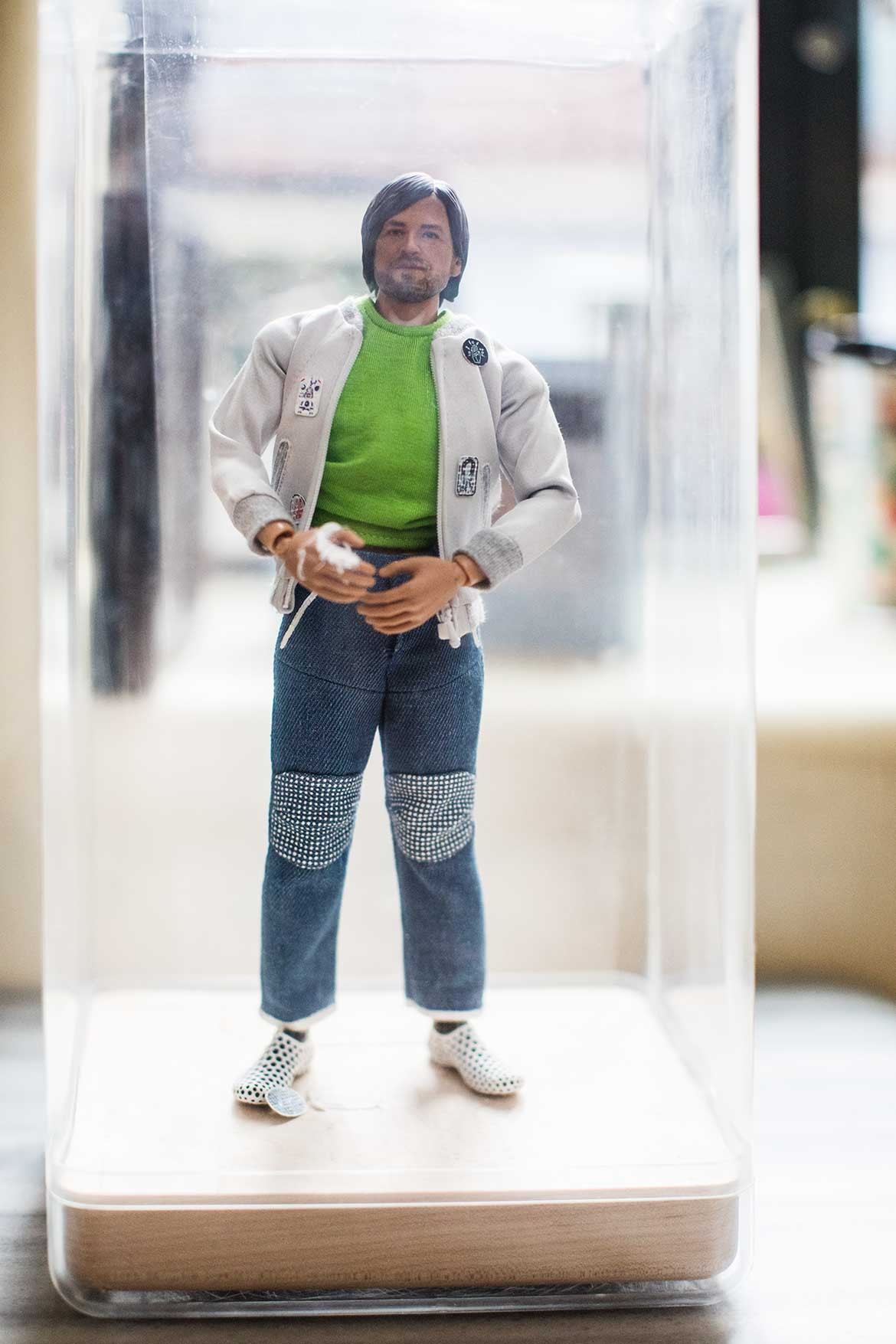

Like Marc, Richard studied jewellery design though ended up becoming one of his generation’s most notable graphic designers. He collaborated on iconoclastic t-shirt label, Mambo, before joining forces with pro skaters Peter and Steven Hill in the formation of streetwear brand, Mooks. Marc became a de facto Mooks brand ambassador, sporting their signature overalls around the world, to even the most swanky events. Nowadays, Marc designs a line for Dutch denim brand, G-Star, with significant input from Richard.

“Philippe Starck made an interesting comment in the early 1990s,” recalls Richard. “He was a big fan of Marc, put the Lockheed lounge in one of his New York hotels, and he said something like ‘Marc is the first one to explore the interior of an object.’ And if you look at the Orgone, the Embryo, the Event Horizon and so forth, that’s true.”

ST: I was always a bit worried that the hollow legs of the Black Hole table would end up full of crumbs.

RA: I’ve got one of the Black Hole tables actually.

ST: Have you ever tried vacuuming the legs out?

RA: Well, in the original version the legs are totally hollow but in the later versions they’re more shallow.

ST: Problem solved then.

Marc Newson left Sydney for Tokyo in 1987 before moving to Paris in 1991. I would occasionally run into him in the street around République, unmissable in a bright orange leather biker jacket by Yohji Yamamoto.

(A gift from the designer in return for Marc modeling in one of his Tokyo shows.) Lank ponytail hanging down to his waist, a seemingly eternal tan, he was like a samurai surfer boy let loose in the City of Light.

For the past two decades, he’s been based in London, where he lives with his fashion stylist wife, Charlotte Stockdale and their two daughters. Marc designed the interior of their 1340 square-metre apartment which sits in the same building as his 15-person-strong studio. It’s a cross between a streamlined Swiss chalet and a baronial hunting lodge, part Marc’s aesthetic, part Charlotte’s. (Her father is Sir Thomas Stockdale, 2nd Baronet of Hoddington, and her Colefax & Fowler covered sofas and zebra-print rugs, she’s referred to as “a little bit of Hoddington in London.”)

Marc Newson has spent 30 of his 53 years living beyond Australia’s fatal shores. He has a family in London, an estate on a Greek island, and is a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE). He retains his Australian accent, but has a penchant for the third-person singular pronoun. All those long weekends at Hoddington, one assumes. How apt is the moniker, ‘Australian designer’?

Even when I first interviewed Marc in Paris all those years ago, he was adamant that he was a designer who just happened to come from Australia, not the designated ‘Australian designer’. He retains that stance today.

“The design industry is completely and utterly global. There are no boundaries. You don’t see that in the music or film industries, even art is not so geographically non-specific. So you’ve really got to travel. That said, I think Australia was a very different place in the late 1980s early 90s than it is today. If I was doing the same thing there now I’m not sure I would have left, to be honest. Maybe there would have been enough stuff to sustain me. My desire to leave was not so much just to leave it was about exploring different ways of doing things.”

Marc Newson

marc-newson.com

Photorgaphy by Richard Boll

As seen in Habitus #37