Vienna, the summer of 1977, a young man is seated on a dark charcoal velvet couch in an upper room of the Kunsthistorisches Museum staring at Titian’s Nymph and Shepherd painted some 400 years before. He’s been there every day for a week now, mesmerised. Sunlight gently dripping from skylights overhead, he’s absorbed in the oscillations of luminosity as clouds pass over the sun. Outside, across the topiary of the Maria-Theresien Platz, atop the Natural History Museum is a statue of Captain James Cook, erected in 1771 as a symbol of a new age of discovery. Our young man is in Vienna on a very different kind of quest.

“The room was breathing, all the information would slide away into the gloom, a dim obscurity. Then the sun would come out and all of a sudden you’d see this opalescent flesh start to sparkle.” The young man was Bill Henson, the Titian his obsession.

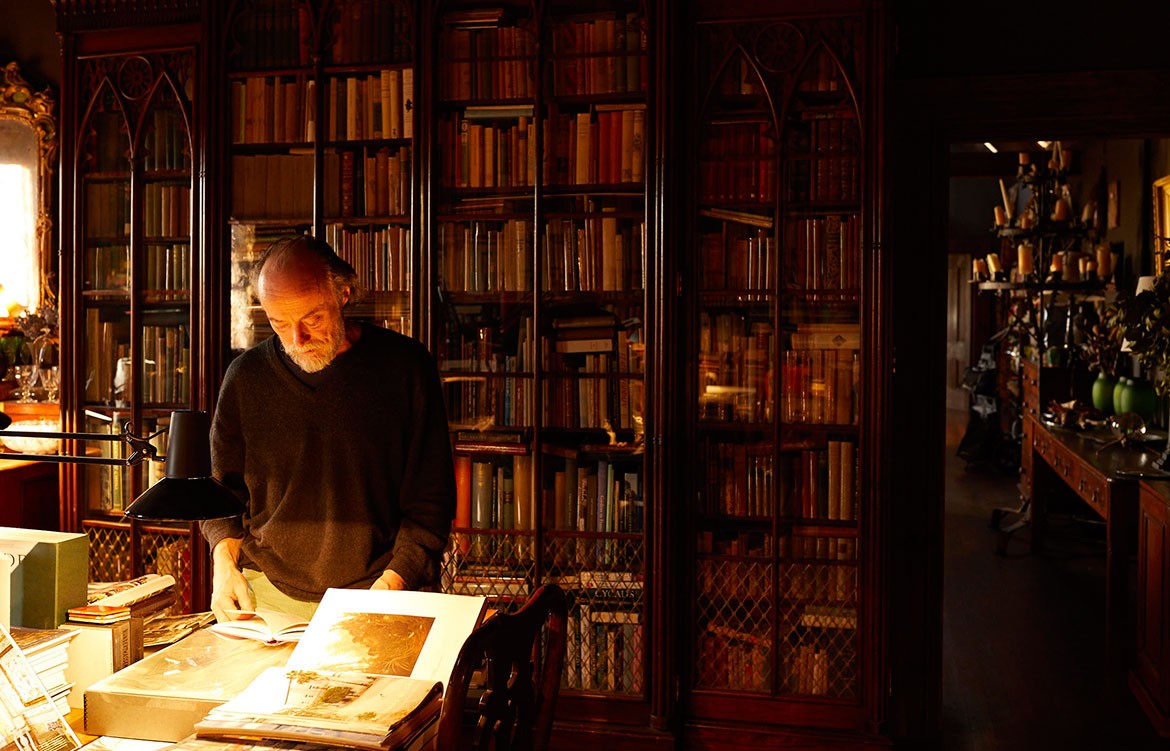

Forty years later we’re seated upstairs in Henson’s grotto of a loft in the inner Melbourne suburb of Northcote. Over his shoulder an English pastoral painting in the style of Turner emanates from a wall painted a velvety brown-black, the shade Bill suggests galleries employ to best offset his work. He’s wearing what appears to be the same pale green corduroy trousers and grey sweater he was wearing when I visited him a week before to begin talking about this story. “I think the hole’s bigger in this one,” he muses, tugging at the left sleeve and confessing he always buys the same thing. A knitted tea cosy, a snatch of spindly japonica, disparate trinkets; the setting is at once humble and sumptuous, a compelling paradox I’ve come to recognise as very Henson.

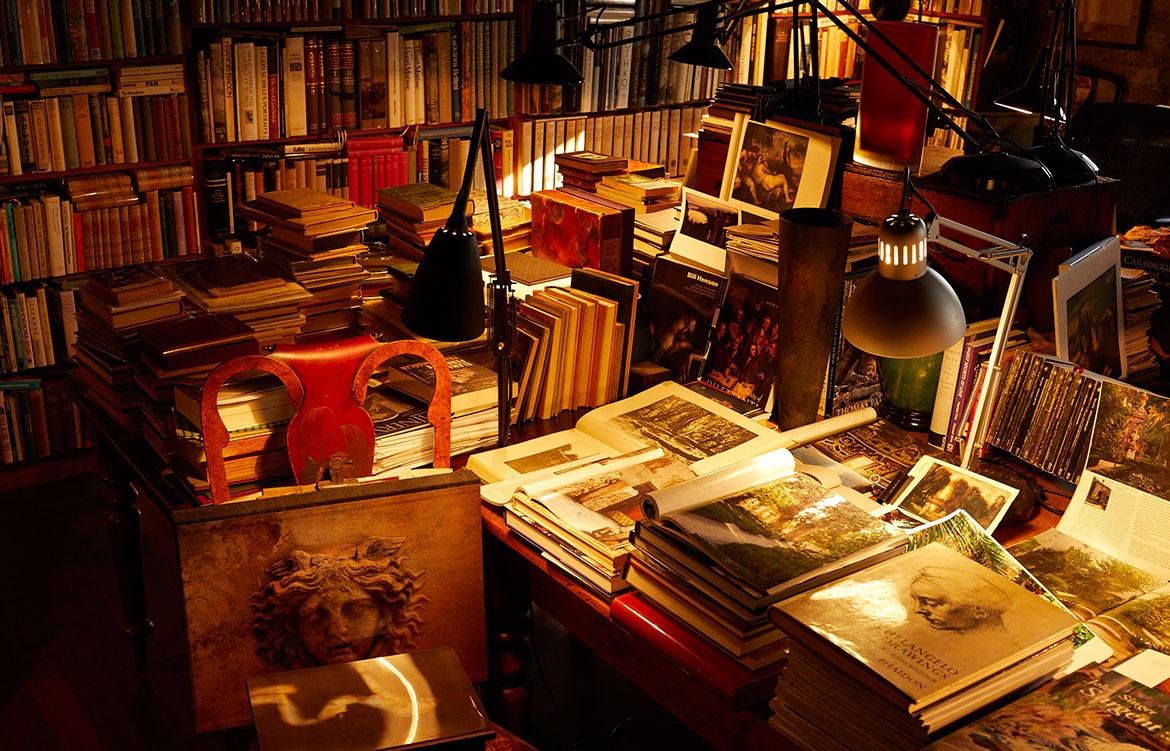

Next door, his library is not so much lined with books as it is brimful of them. A gaggle of Anglepoise lamps crane over volumes stacked in the centre of the room. The mix of natural and incandescent light creates an amber glow, a heady honey hue in which everyone and thing looks pleasing. The lamps have not been moved since my previous visit, but the books laid open at various points around the room have changed. It’s easy to imagine Bill Henson wiling his days away, swooning from one first edition to the next. The vision would be fey if the reality weren’t so intense.

“In that corner over there,” he says, indicating a black swivel chair beneath a west-facing window where the vigour of afternoon daylight creates greatest tension, “that’s where I sit with my feet on the desk and look at my contact proof sheets. I have music going sometimes, and I have a white Chinagraph pencil and I have my magnifying glass and I go back and forth over them and I might do that for a day, a week, six months or maybe a year. I will have a wonderful time trying to sift out the shots I think are going to work when I blow them up.”

The blowing up (not “enlarging”, Henson’s is a frank lexicon) happens downstairs in what would best be described as his atelier – if an atelier can be kitted out with rare books, museum-grade antiquities, and dozens if not hundreds of large format photographs sitting one behind the other on robust timber easels. Hanging from an iron I-beam, two wooden gymnast rings hover on leather straps above a satiny, poured concrete floor. Bill Henson is one of Australia’s greatest living artists, certainly our most cerebral – and perhaps, somewhat surprisingly, our most corporeal.

For most of his adult life, Bill’s been a runner, clocking up at least ten kilometres a day “as a form of relaxed meditation”. For the past decade he’s worked with a personal trainer by the name of Ozgur three days a week, two hours a day. Plus the high-speed, twenty-kilometre bike ride from Northcote to the gym in South Melbourne and back. “The brain is in the body, and when working out it’s as if what Nietzsche referred to as the great intelligence of the body takes over. You switch off some intellectualised aspect of life for a time.”

ST: So you have a body of steel?

BH: I don’t know, it’s got all this old skin on it.

ST: When you’re photographing, do you reach the same sort of intensity as you attain in your physical training?

BH: It’s very intense in that it’s a big deal which means that I’m quite anxious. There’s a high level of anxiety mixed with anticipation for which the Germans have a perfect word, erwartung. I’m not necessarily outwardly stressed, it’s just that it’s almost impossible for me to pick up a camera. I pick up a camera when I have absolutely no choice. It’s not a pastime where I play around.

That pilgrimage to Vienna in his early twenties happened shortly after Henson first exhibited his work, part of a group show. He’d been enrolled in the Photography department of the Prahran College of Advanced Education under the tutelage of noted portrait photographer, Athol Shmith. While Shmith and fellow Prahran College director John Cato recognised Henson’s very evident talent, his repeated absenteeism and failure to complete assignments led them to recommend he ditch academia. “I’d rock up after not being there for three of four months and they’d just shake their heads and say, We love the pictures you’re making but there’s no need for you to be here.” He didn’t need to be told twice.

Released into the wild, the artist as a young man began taking portraits. Of schoolgirls, of passersby, of budding ballerinas. That first exhibition incorporated images shot at a dance class held in a suburban church hall. “The light was astonishing. The people in the photographs could have been doing something else, gymnastics, painting, it didn’t matter to me what they were up to. I made selections, zeroed in on a couple of particular people who had a presence, a bearing that intrigued me.”

In a letter dated 14th October, 1974, one perspicacious collector, St Kilda gallerist Bruce Pollard, contacted Henson via the office of Athol Shmith offering to pay him $25 for the picture titled Carlton Afternoon, including delivery (“it would be great if you could take it to him,” wrote Shmith’s assistant).

Today, of course, Bill Henson is one of the most celebrated artists in the land. And while his work has evolved from those hazy, grainy early days (“Sarah Moon copied me!” he quips, though I suggest they’re more Deborah Turbeville), the intensity of his gaze has never waivered. “In the end it comes down to beauty. I love beautiful things. No, that sounds weird, I’ll rephrase that. It’s all about what attracts the eye, and that varies tremendously from one person to the next.”

ST: Are all your senses engaged, or is it uniquely the visual that concerns you?

BH: We first covet with our eyes, it’s a longing for things. You can be looking at a sunset, or a beautiful piece of fabric, or a beautiful object or you can be looking at a beautiful person. To you, they have a certain grace, the way they move, the way they turn a corner of a street. It could be anything, but it’s rich. For better or worse I’ve always been drunk on the look of things. Drunk on the weather and the light. At school, I was always picked last for the football team because I couldn’t keep my eye on the ball. I was too absorbed in what was happening in nature, too busy looking at what the light was doing in the trees, or watching the occasional kid who just happened to move in a way that was distracting, disconcerting.

For Bill Henson, distraction and disconcertion are positive forces which, if harnessed with a deft hand and adroit eye can result in an extraordinary frisson. It’s the shiver of early onset Stendhal syndrome I sense whenever I encounter his images.

Yet distracting and disconcerting are also charges levelled at Henson’s work, oft times arising from an irrational puritanical reaction, a self-imposed verboten. Spending time in his studio, immersed in the viscous beauty of his imagery I had to confess to having no language to describe the effect. “Good,” he says, looking pleased.

“Whether it’s his landscapes or his still lives or his nudes, they all speak to me about the beauty of living and the pain of living,” says art collector Morna Seres, a long time admirer of Henson’s work. “There’s something in the cusp of pubescence, the state between childhood and adulthood that really exercises that. Whether he has one or two or five figures in a picture, they’re very alone. They’re in their own space, there is connection but then there isn’t. It reminds me of my own aloneness, it speaks to the drama of the human condition.”

Henson’s home is where he plays out the drama of being human with his partner, painter Louise Hearman and their Staffordshire Terrier, Mr Pigs. It was Hearman who found the abandoned, double-height, red brick former stables dating from the 1880s. “It was essentially sections of rusting corrugated iron roof tacked onto some very old, diesel- and dust-encrusted beams,” Henson remembers, “and on a windy day the roof breathed in and out like a lung.”

But the light was magnificent and the surrounding paddocks made it seem a bucolic idyll. Since then the meadow has been occupied by townhouses and the once desolate High Street strip mall has given rise to a new hipster enclave. A little over a decade ago, they bought the neighbouring property, converting the hangar-like garage into a semi-alfresco photo studio and trucking in a luscious garden of fully grown palms. Perfectly isolated from the outside world, it’s a little bit of Palermo on the 86 tramline.

Henson and Hearman met when she was a student at the Victorian College of the Arts and he had been invited by the dean to talk to the Photography undergraduates. “I thought, Well, I’m not going to talk to them about photography. I’m going to play music to them. So I just played classical music to them in the darkroom. Louise was upstairs in the painting studio, heard the music and it drew her down the stairs. I smelt her before I saw her. She was going through a grunge phase, hadn’t washed for about six months, was full-on the filthy art student. And as she came along the passageway I smelt this gin-wine-one-hundred-percent New York subway dero…”

ST: Was it love at first sight?

BH: Not quite. She said she was interested in music, so I gave her a list of things. I think I was playing Second Vienna School, so Berg and Webern and Schoenberg, and she went on her way. I came back to the VCA from time

to time to do a bit of teaching, and we just became friends. That was 1981 or ’82.

ST: Gosh, you’re an old couple now.

BH: (Assumes cod British accent) Oh yes, terribly old, terribly old-fashioned.

Hearman’s portrait of Henson garnered her the lucrative Moran Prize in 2014. Like most of her work, it is typically described as ‘dreamlike’ and ‘cinematic’ – words that are often also attached to Henson’s photographs. In many ways, the pair seem to inhabit parallel worlds, he with his cavernous atelier ground-floor left, she with her airy studio ground-floor right; a steep, narrow, black-walled staircase bisecting the building between these two creational zones.

To be clear, Henson and Hearman have nothing of the old couple about them. In fact, they’re quite childlike – perhaps more Enfants du Paradis than Enfants Terribles but either way happily wrapped up in a world of their own devising. In both the physical and metaphysical senses. Their shared home is a zone of its own, a high-walled retreat, an oasis, a bastion. A place that, should the high, metal gate slide aside and Mr Pigs waddle his welcome to let you in, you enter as if into a state of grace.

Asked to describe his own work, Henson quickly slips into faux art critic shtick, and mugs: “…‘Something about what goes missing in the shadows animating the speculative capacity in a way that highlights… something about just the fragment suggesting more than the whole….’ They’re all clichés but in fact they’re no less true for being so.”

Despite himself, Henson has evoked the very genius loci – the elusive spirit – of this magical place in a gritty side street off a busy thoroughfare that leads to a suburban nowhere. It’s the invisible presence in so many of his images, a place/non-place that exists in the gloaming, entre chien et loup – between dog and wolf, as the French call the shadowy twilight zone of endless possibilities.

Photography by Anthony Geernaert

*With thanks to Joan Didion, Blue Nights