Above: Designer John Spatchurst, at work in his meticulously created home environment.

Heading down the windswept street to John Spatchurst’s inner-Sydney Victorian terrace, there is nothing about the dusty façade or the dry leaves blown into corners that singles it out for special attention. But step inside, and the meticulously crafted interior makes for a compelling contrast.

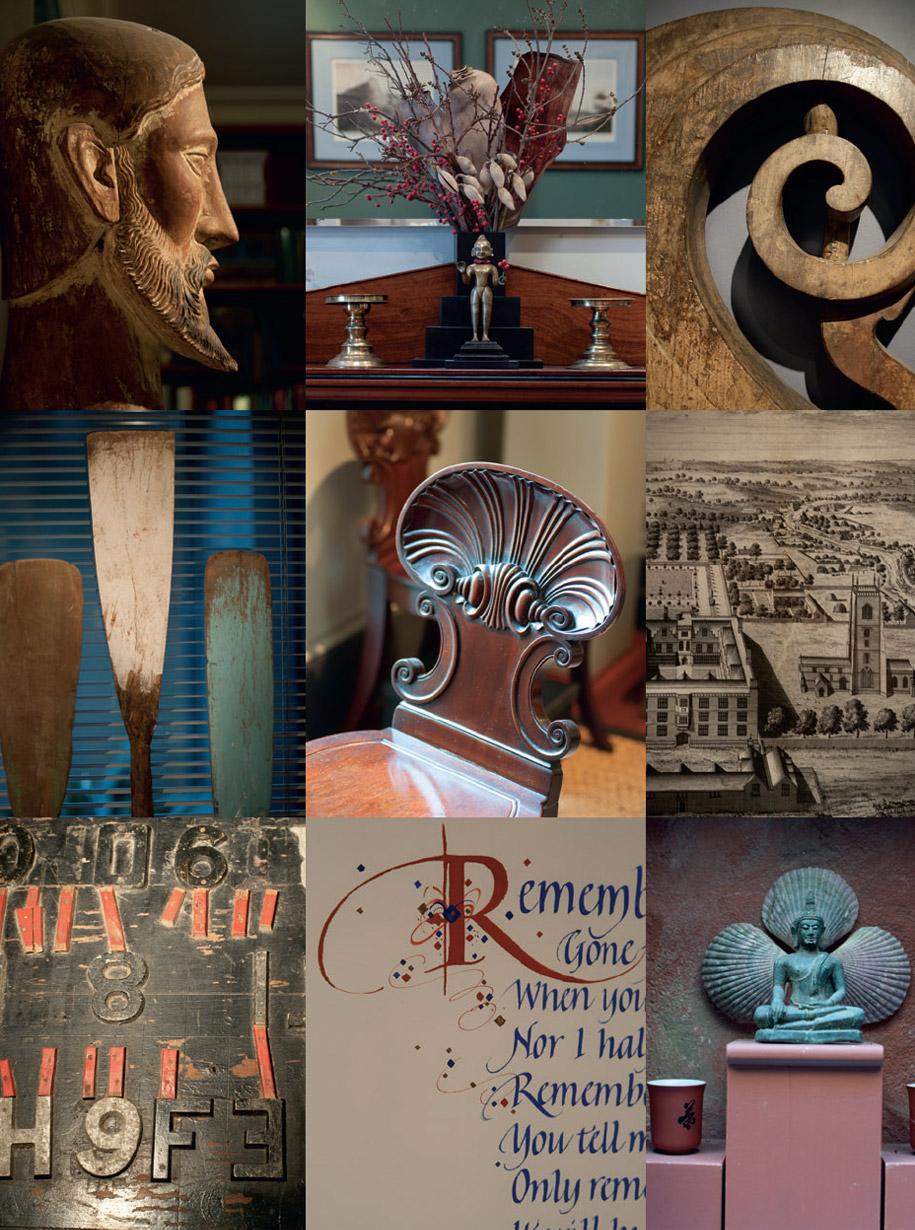

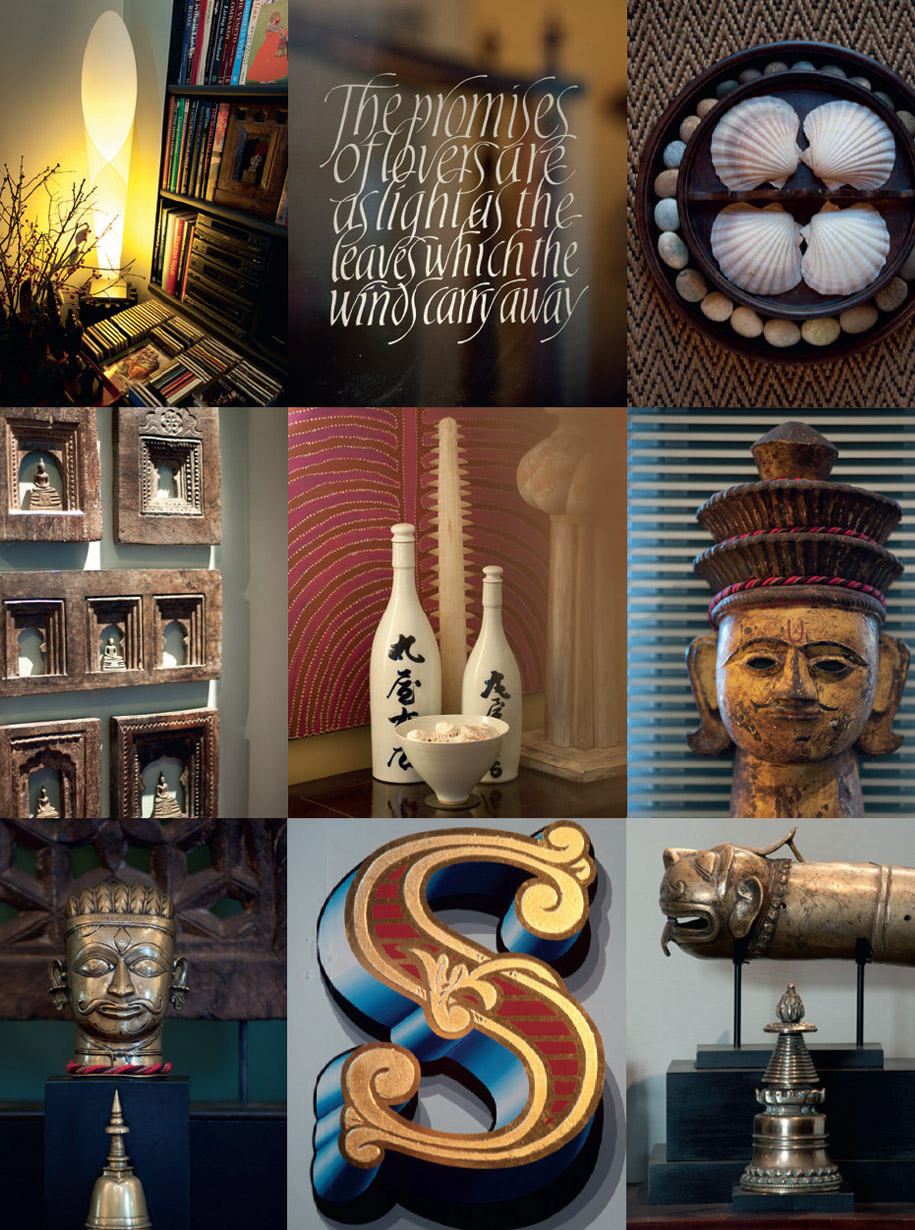

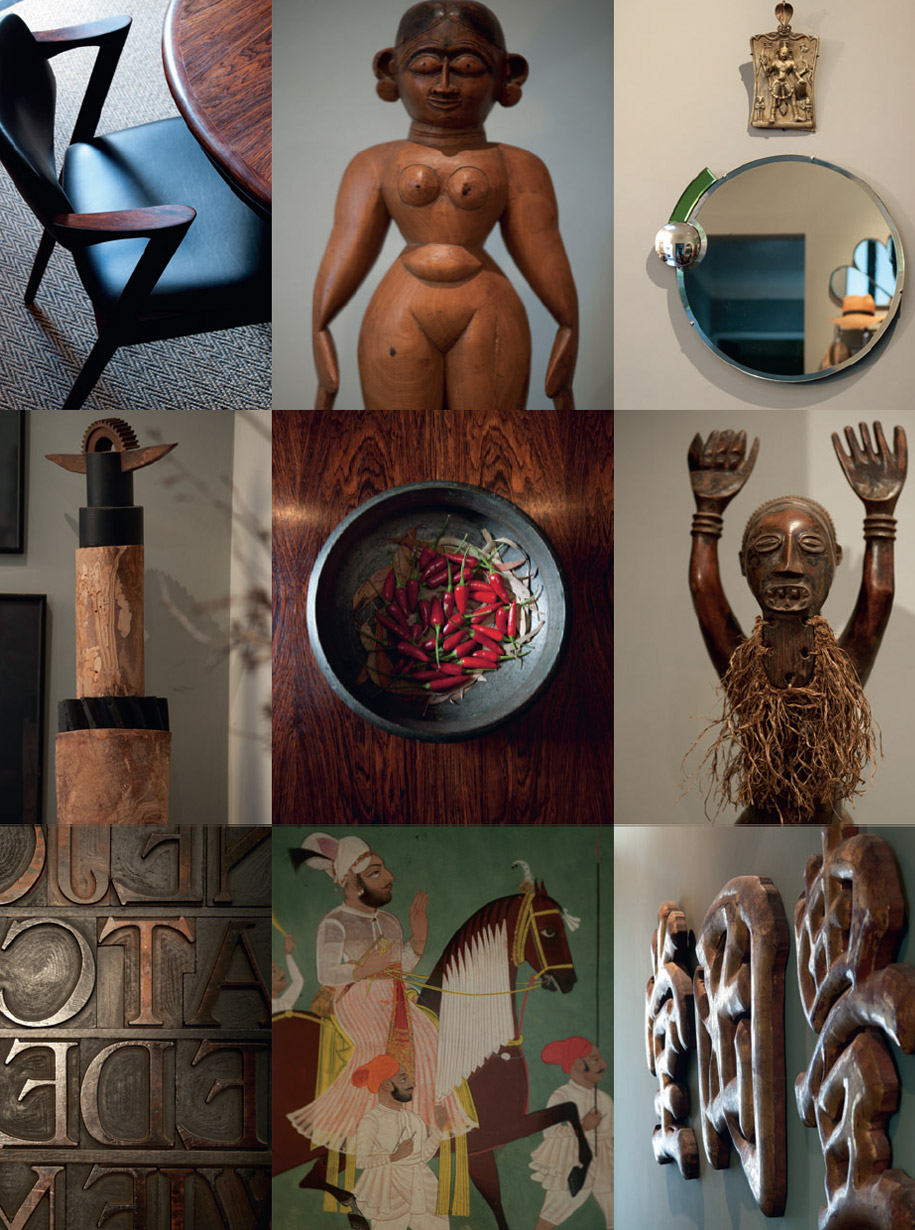

A sombre-toned hallway opens on to a compact double dining and sitting room, a space cleverly contrived to create simplicity out of complexity. A feeling of order, harmony and calm pervades, yet everywhere the eye turns, it finds rich and varied detail: the lustre of antique Mahogany and the striking stance of tribal sculpture. There are architectural prints, Indian bronzes and John’s own sculptures, along with lamps, decorative artworks and shelves full of books, with mirrors strategically placed to amplify the whole. Other rooms in the house are equally stocked with treasures and just as serenely ordered. John’s diverse but highly selective interests, which are reflected in his collections, include Greek Revival and

A sense of serenity prevails in the entry hall and front rooms of this compact inner-Sydney terrace houses.

Anglo-Indian furniture and artefacts, along with Japanese and Danish furniture and Asian calligraphy. The quality and variety of the individual pieces, and the care with which he displays them, is a subtle triumph.

The interior is an artful expression of its owner in every way. As a young teenager growing up on the fringe of London in the early 1950s, John used to ride his bicycle around the countryside to look at the grand houses and churches. In the wake of World War II, apparently, one English country house was demolished every two and a half days, its interior stripped, its staircases burnt and its contents sold off.

John’s exposure to this desecration, and to the wealth of material history it laid open to him, fired his passion and he spent his pocket money collecting artefacts in antique markets and junk shops. He also lived near to and often visited Dulwich Picture Gallery, one of the most beautiful buildings designed by acclaimed English architect Sir John Soane, whose work remains one of his strongest influences.

Diverse objects collected over a lifetime are carefully juxtaposed and displayed to handsome effect.

With thoughts of becoming a painter, John finished art school in the late 1950s but subsequently worked in advertising, film and television in London, and in graphic and set design in Australia, before establishing his own graphic design firm in Sydney in the 1970s.

Creating his home environment has brought together the sum of his long experience as a typographer and exhibition designer with his love of architecture, art and furniture. (John is vice-chairman of the NSW Furniture History Society.) “It’s all interconnected,” he says, “and that’s what’s so good about being a designer because your private life and professional life is so intermeshed.”

Artefacts with historic, cultural or religious significance are placed together with a designer’s eye.

The skill that is required to bring such diverse objects together into a harmonious whole might well be intuitive, but John offers a more concrete explanation. “As a graphic designer and typographer, line is very important to me, and if you look at the things I collect, they all have lovely lines. I love Indian miniatures, for example, because they’re all about line.” He cites the strong linear quality or graphic element in Greek Revival architecture (Alexander ‘Greek’ Thompson is another favourite), Anglo-Indian and Danish furniture, and calligraphy as further cases-in-point.

Then there’s the way he physically puts the pieces together. “As an exhibition designer, I like to display things in a context that shows them off,” he says.

Sited along a corridor on the lower floor, John’s work desk takes full advantage of limited space.

John recalls a revelatory visit in the 1960s to Kettle’s Yard, the Cambridge home of modern art curator and collector, Jim Ede, which is now a substantial museum and gallery. Accepted notions of interior design at the time required a polite consistency of style, whereas at Kettle’s Yard, John found a living space that vibrantly expressed individual taste. Here, an eclectic combination of modern paintings and sculpture, furniture, glass and ceramics of various eras and styles was combined with objects both old and new, found and made. “He mixed everything up,” says John. “Kettle’s Yard demonstrated more than any other post-war interior that it’s not what you have but what you do with it that makes a satisfying environment.”

The sheen and burnish of wood and metal highlight a sensitivity to surface quality.

Exploring the way carefully selected but assorted items in his own home can create excitement through their juxtaposition, John delights in the way particular images or tableaux are created, ‘still lifes’ of sorts, in which conversations are generated between the furniture and objects in them. He believes this re-contextualisation enriches and enlivens a space because it offers new ways to look at things and new opportunities for consideration.

Found objects exhibited at Kettle’s Yard also made a lasting impression, and for some years John has been using them to make his own sculptural forms. “I love found objects. You put them together in a way in which they talk to each other or play off against each other to create a whole new meaning.”

A 19th Century Ceylonese tent bed rules the bedroom, with a Sri Lankan mask of Naga Rassa, the snake demon, behind.

Perhaps the critical distinctive element to the quality of his home’s interior is the fact that each highly considered object is chosen with a deep knowledge and affection for both its visual style and its cultural significance. There is no convenient fill – the integrity of the decision behind every inclusion is absolute.

“A house like this, with time, takes on a patina that cannot be achieved by mere decoration,” he says.

Left: Functional items as collectibles are displayed on a 1930s French chrome-plated hall stand.

Right: One of John’s own artworks complements a collection of Indian chapati rolling pins.

“What I like about having the things around me that I do, is that they actually excite me. You choose them because you really like them, and if they don’t last, if they no longer give you that thrill, you get rid of them.

“Some things go on and on, because there’s always something new to see: like the sideboard – I would never part with that – or the hall chairs, or these pictures…”

At the same time John often scans the auctions for new thrills, and the interior continues to evolve, as both a remembrance and a living expression of his fascinations, pastimes and personality, the intense visual and cultural preoccupations that inform his life.

Photography: Anthony Browell