In 2016, The New York Times Style Magazine published an article with the fittingly stark headline “Brutalism is Back”. Indeed, Brutalist architecture is enjoying a renaissance, emerging as the new darling of social media – particularly Instagram, where pictures of sharp-cornered buildings cast in stunning chiaroscuro abound. A quick search of ‘Brutalist Architecture’ on Pinterest yields pages upon pages of results, their contents a blend of archival images and contemporary photographs.

But something seems a bit odd about capturing brutalist architecture in the digital world, a medium that feels almost too fleeting and lightweight to sufficiently encompass the scale and gravity of the movement. Find below our top 5, heavy-duty books on the matter.

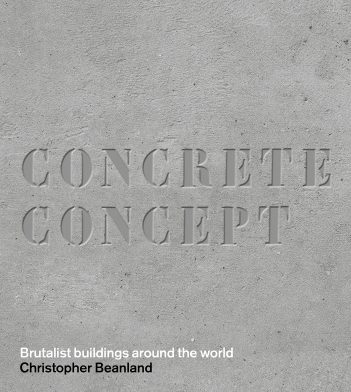

Concrete Concept: Brutalist Buildings Around the World / Christopher Beanland (Frances Lincoln)

“Why do you like these ugly buildings?” Concrete Concept asks readers. The question comes right off the bat and echoes throughout the building’s many pages – at 192 pages and nearly 1kg, the book is a veritable tome that serves as a meaty introduction for those new to brutalist architecture. Brutalism is arguably one of architecture’s most divisive styles, with few others seeming to inspire the same level of clearly articulated, much stewed-upon vitriol.

In Concrete Concept, Beanland takes readers around the world to 50 of what he deems the best examples of brutalist architecture to come out of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. The book’s earliest pages set the scene with an ‘A-Z of Brutalist Architecture’ that provides a helpful guide to the jargon that is often bandied about in discussions of brutalism. Ever wondered what Expressionism was? Or World’s End? Well, wonder no more. Assertive, imposing, and sharply laid out, Concrete Concept demonstrates the fearless and unmatchable aesthetic of brutalism, and gives readers plenty of explanations for why we like it so much.

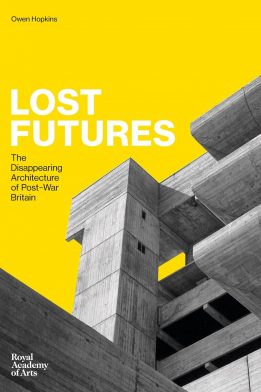

Lost Futures: The Disappearing Architecture of Post-War Britain / Owen Hopkins (Royal Academy Publications)

British architecture historian, writer, and curator Owen Hopkins is well known for his surveys of architecture that are unique for their perspective of an insider looking out. The former Architecture Programme Curator at the Royal Academy of Arts, Hopkins seeks out topics that fall outside mainstream architecture canon – Mavericks: Breaking the Mould of British Architecture explored those working outside contemporary norms and From the Shadows documented the life of Nicholas Hawksmoor, a key London church architect relegated to the footnotes of architecture history.

In his latest effort, Hopkins turns his attention to the brutalist architecture of Britain between 1945 and 1979. Drawing parallels between brutalism and the optimism of postwar society, Lost Futures captures the many faces of the style in everything from housing to factories, civic buildings, commercial buildings, and industrial structures. Hopkins then tracks the progress – and in many cases, decline – of these buildings as time has progressed. Lost Futures casts brutalist architecture as a clear product of its time, and is telling in its reveal of the many ways that brutalism is disappearing through alterations, additions, and demolition. The increasingly private, neoliberal cities of today are edging out the civic-oriented postwar architecture, and doing so at a rate that is, well, brutal.

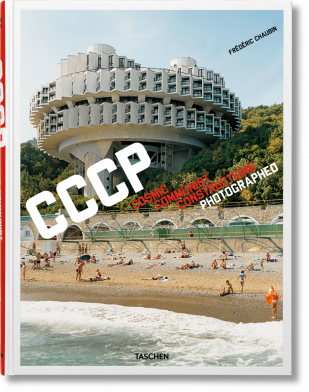

Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed / Frédéric Chaubin (Taschen)

It’s virtually impossible to talk about brutalism without mentioning communism. The movement’s utilitarian, functional drivers and uncompromising nature made it the style of choice in many European communist hot spots during the mid- to late 20th century. Quick, cheap, and efficient to build, brutalist buildings are still considered by many as vestiges of the communist era, where they took the form of civic and residential buildings of a grand scale that spoke to the hope and social equality touted as benefits of communism.

Ninety buildings in 14 former Soviet Social republics are documented in the book, whose spreads are in glossy, full bleed colour. The double spread images depict buildings that are stark but not grotesque, and vibrant in a way that challenges many of preconceptions about the staid, depressing nature of Soviet architecture. Once a utilitarian feature, the no-nonsense construction of Soviet brutalist architecture is now at their core, allowing them to remain standing today as monuments to a bygone age.

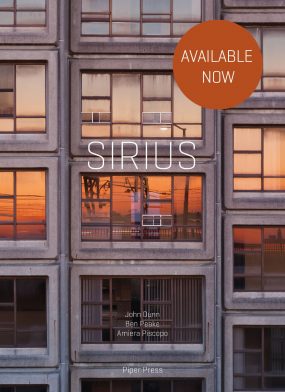

Sirius / John Dunn, Ben Peake, & Amiera Piscopo (Piper Press)

What Australian interested in brutalist architecture – and, for that matter, cities at all – doesn’t know about Sirius? Tao Gophers’ public housing project in the historic The Rocks has been making shockwaves throughout the Australian architecture world for the past few months as a failed bid for State Heritage Listing prompted the NSW government to put the tower up for sale. The building is one of Sydney’s most iconic pieces of brutalist architecture, recognisable for its prominent position on the city skyline and resemblance to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67.

The tale of the building has captured the hearts and imaginations of many, and mobilised architects, designers, and those interested in the urban realm to protest the treatment of an important part of Sydney’s social and architectural history. In Sirius, the authors trace the history of the building back to the iconic 1970s Battle for the Rocks and Green Bans, two key shapers of the built form of the city today. The richly illustrated, evocatively written book is excellent for giving an understanding at a granular level of the social significance of brutalism, particularly within an Australian context. Proceeds from the book’s sale support the Save Our Sirius campaign, a citizen group fighting to preserve the brutalist icon.

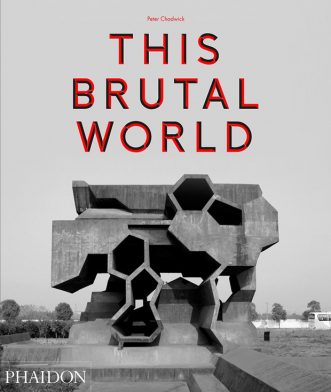

This Brutal World / Peter Chadwich (Phaidon)

This Brutal World, a sleek, glossy coffee table book about brutalist architecture is arguably the final mark of brutalism’s acceptance into the mainstream architecture canon. Treating the style not as a historical quirk or quaint social project, it instead portrays it with the cool gravitas accorded to other movements such as minimalism, internationalism, and sustainable architecture.

Peppered with book quotes – including one from Orwell’s 1984 – that tap into the imagination and dystopian nightmares that brutalism’s stark aesthetic often conjures, This Brutal World portrays brutalism as something very much alive and thriving. Unlike the other books on this list, it is less a retrospective of brutalist architecture and more a manifesto: Chadwich is more concerned by Brutalism as an aesthetic than a movement per se, and includes buildings by Zaha Hadid and David Chipperfield alongside the classic Breur, Kahn, and Le Corbusiers. Highly graphic and stylised in monochrome with red accents, This Brutal World is a bold, teasing statement of what is still to come for brutalist architecture.