The land around Finnon Glen is an idyllic microcosm of everything that’s wonderful about the Victorian bush. A narrow unsealed road winds its way up a hill; magpies warble and gargle from branches and fence posts; car tyres crunch over the yellow, sandy gravel, and an occasional low, languorous moo drifts on the breeze, offering a timely reminder to close the livestock gates after you pass through. As the road climbs, paddocks, barns and distant peaks disappear and re-appear between stands of eucalypts. Some of the trees are blackened and lifeless, but many more are vibrant and verdant, their trunks coiffured in dense new growth. Slowly, the views open up and the full majesty of the setting is revealed. To the north and south, the lands drops away into shallow valleys, and then, on all sides, it rises up again into an almost continuous ridgeline; a glorious 360-degree panorama of forest and farms sparsely dotted with sheds and houses.

But here, as in most parts of Australia, the bucolic idyll can never be taken for granted. Overlaying the names of towns onto the undulating topography of the surounding district casts the place in a new light: to the south is Healesville; to the east, Narbethong; to the west, Kinglake, St Andrews and Strathewen. For many, these names still resonate with memories of the Black Saturday bushfires. Three years on, most of those who chose to stay and re-build now have new homes. The MacKinnon family country house – Finnon Glen – is one such building, risen from the ashes.

In the aftermath of Black Saturday, the architecture fraternity contributed in many ways, but perhaps most notably with the establishment of the Bushfire Homes Service (BHS). Through the BHS, people who had lost their homes were given access to architectural services and could choose from nineteen architect-designed house models. The MacKinnon family – guided by one of their own, interior designer, Fiona Lynch of Doherty Lynch – chose a strongly rectilinear design by Jackson Clements Burrows Architects (JCB).

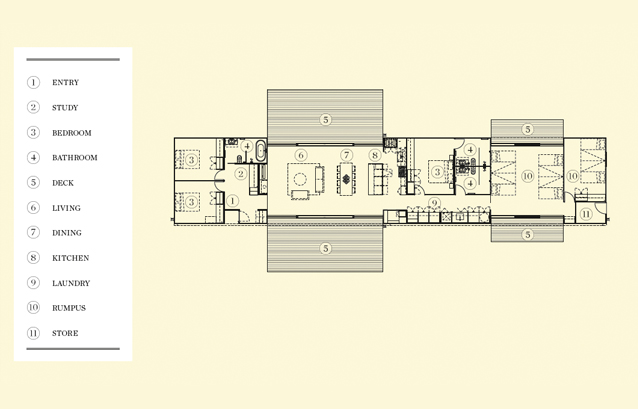

JCB’s original model was generic, in the sense that it met a broad brief, but could be easily adapted to meet the specific requirements of site, of fire resistance and of individual clients, and architect Tim Jackson – the “J” in JCB – was instrumental in creating a plan that met the family’s needs. Thanks largely to his design tweaks – perhaps most obviously, the transformation of an undercover carport into a combined rumpus and kids bedroom – Finnon Glen can accommodate, in myriad configurations, three different generations, four separate family groups and seventeen grandkids.

The house as it has been built is long and skinny, and, clad in metal sheet roofing, sits unobtrusively in the landscape like some sophisticated farm shed. The long sides open up to the north and south, giving almost every internal space access to incredible views and northern sun, and, despite the narrow footprint, the interior doesn’t feel at all constrained. The views help with this, by drawing attention beyond the physical boundaries of each room. But the feeling of openness is also a result of a cleverly compact program. Every space seems to have a function, and some have several – for example, part of the built-in storage along the wide hallway is given over to a hidden laundry; the space inside the front door doubles as a study; and the large kids’ rumpus/bedroom opens up to timber decks on both sides to become an indoor-outdoor play zone (a large acoustic sliding door affords privacy and preserves parental sanity).

While Jackson refined the plan, Lynch and design partner, Mardi Doherty, focused on the interior. In keeping with the brief for a family holiday house in the country, the feeling is relaxed, natural and warm. Timbers, tiles and finishes have been specified for honesty of expression and, of course, given the rotating population of little people, for durability. These qualities are established upon first entry, where Spotted Gum (which has been used to clad the external entry nook) flows into the interior as both floor covering and cladding for the front of the kitchen bench. Tiles are used to great effect, but again without disrupting the overarching fuss-free vibe – in the bathrooms, a subtly tactile hexagonal, parchment-coloured mosaic recalls the patterns of bees wax or reptile skin; in the kitchen, a feature tile to the splashback echoes the peeling bark of a gum tree.

Unsurprisingly, given Lynch’s past history working with John Wardle, joinery is the knockout feature of the interior. The selection of materials and finishes here, particularly the exquisitely grained Japanese Sen Ash panels and moleskin-coloured laminate, are consistent with the broader palette within the house; and black laminate kitchen cabinetry, deftly crafted with exposed ply edges, positions the kitchen as the visual anchor for the open-plan living space. But it is the treatment of handles as simple ply extrusions rather than off-the-shelf stainless steel fittings – a seemingly minor decision – that makes the joinery so important to the character of the interior, creating the feeling of a single, cohesive, hand-built space (the tactic of avoiding downlights and using only one light fitting, in pendant and wall-mounted versions, plays to the same strategy). Down the hallway, the joinery adds a sense of fun too, as the combination of off-white cabinetry and black-laminate-clad ply handles re-casts one wall as a super-sized piano keyboard.

The interior is minimal, to be sure, but, where many designers might have plumped for well-worn tropes like The Resort or The Art Gallery, Doherty Lynch has taken a much more honest approach. Their dexterity with custom detailing and intuitive feel for texture give the house a warm, human feeling – it is a place to be lived in, not just looked at.

This human feeling is fitting given the collaborative spirit with which the house was designed and built: various members of the extended MacKinnon family played important roles throughout the process; JCB gave their design, via the BHS program, and Tim Jackson gave his time generously; and Healesville-based builders Overend Constructions provided high-quality services as professionals but also as members of the local community. It was a wonderful team effort. Indeed, we rightly marvel at the speed with which flora and fauna regenerate after bushfire, but the rise of Finnon Glen proves that humans deserve our admiration too.

Text: Mark Scruby

Photography: Sonia Mangiapane, Gorta Yuuki

sonia-mangiapane.com, gortayuuki.com