In 2011, Keiji Ashizawa Design commenced the House S project in a quiet Tokyo neighbourhood. The site of a former Samurai home, the lush vegetation surrounding the home was prized and deeply understood by the owner. As such, the design addresses the dual desires for a home that acts as a natural backdrop to an impressive art collection, as well as equally bringing the surrounding landscape into the home.

Constructed at the north-eastern end of the block to allow a garden to be planted along the south-western perimeter, the three floors of House S are arranged to engage with different aspects of the environment and a neighbouring garden.

A few years after the house was completed, the client bought an adjoining plot of land on the west side of the property, which is now maintained as a garden, also designed by Ashizawa, who sees the project’s evolution as appropriate to such a substantial home.

The garden itself contains two parts, a traditional Japanese garden and an active social space for barbeques and entertaining. As time went on and the garden developed, a conversation began about whether to introduce a room – possibly a tearoom, possibly a guest room. “The client wanted something more relaxed and less tied to a function… a place where the garden could be enjoyed differently, as a kind of hut, as compact as possible,” Ashizawa says, who shares that the room’s use is now mixed and can be for quiet contemplation of the garden, or where the chef sets up during parties.

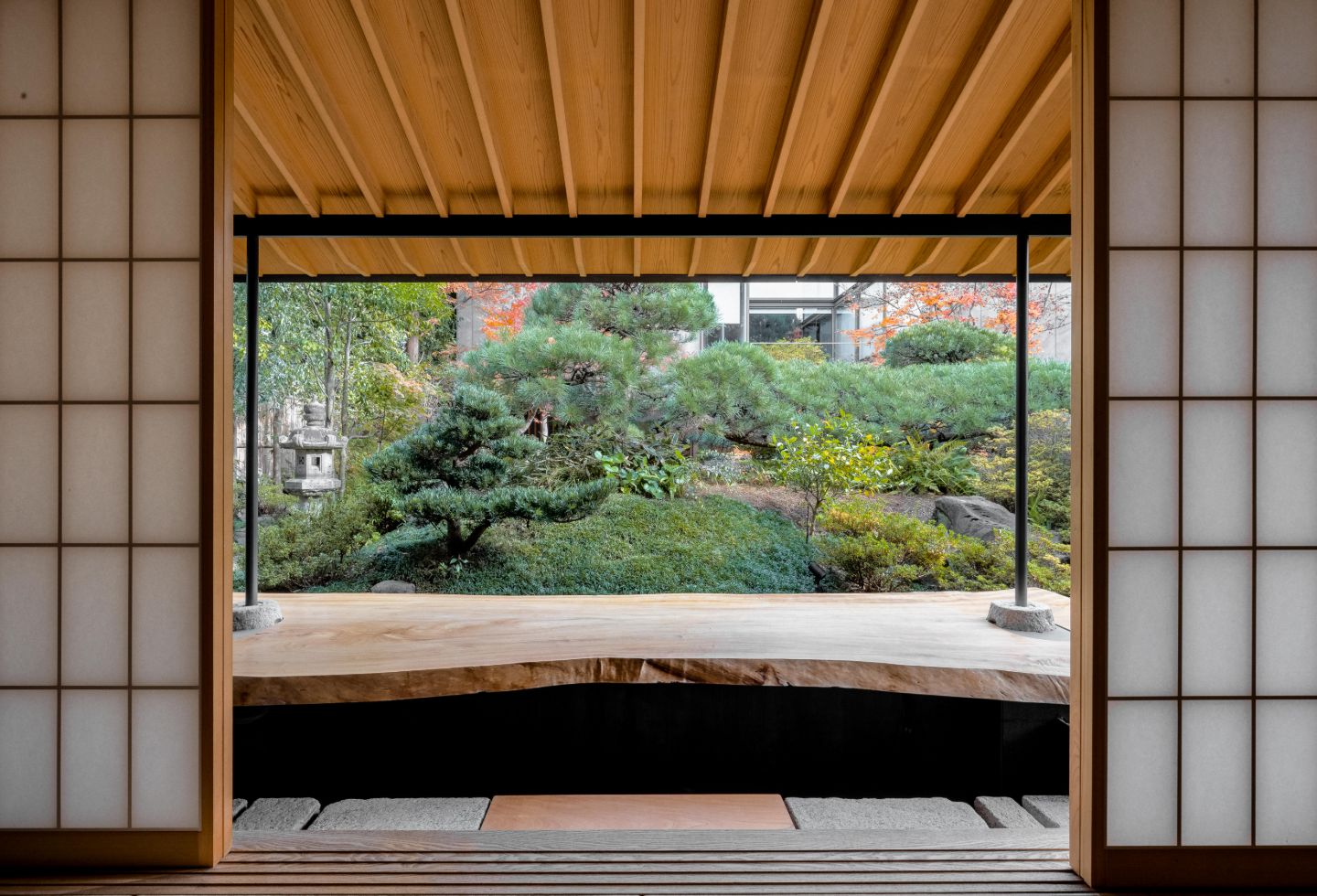

The Garden House has no dictated use, giving it the ability to serve dual purposes, which is innate to the simple nature of the building. Large enough for four tatami mats and a tokonoma (display area), the interior space is intimate but comfortable and is sometimes used as a guest room. The space, however, is expanded by the extended roof sheltering a large timber slab. “We incorporated a piece of camphor wood into the project that the client had fallen in love with,” says Ashizawa.

Locating the site for the Garden House was considered from both how it would be seen from House S and what views it would afford. “A small hill was built in the centre of the garden to create a sense of distance between the garden and the Garden House behind it,” Ashizawa says. As such, only the roofline of the Garden House is visible from the lower floors of House S. Conversely, the garden is the focus from the Garden House with the house only coming into view from the periphery. To a large extent the enveloping nature is the point, with the small hill truncating the view to an immersive experience of the garden. Even the arrival is orchestrated for immersion with paving stones in the surrounding garden leading around the front of the hut before turning back to arrive at the entrance.

The large piece of camphor wood, arranged as a traditional sunken kotatsu (tabletop), is the aesthetic foundation for the project and visually connects the structure to nature. A fine steel frame from the roof overhang aligns with the tabletop, “to create a feeling of lightness” as Ashizawa explains. The steel in turn is anchored to the camphor by stones once used by the client for weighing down pickles at his family home in Kyoto.

The interior is simple with tatami mats, flat cushions in dark grey and a large and sculptural white paper lantern, plus the tokonma in dark grey. Open at the front with narrow shoji screens that slide back to occupy only a small space, the form is fundamentally a hut. But it is intricately considered with a paved hearth of stones that are tonally similar to the pickle jar stones, and one central stone of ochre, extending from below the camphor table to the building’s foundation. A clever design inclusion can be seen where the foundation conceals secret drawers for shoes and the increasingly necessary air-conditioning.

To some extent there is a presumption that a garden house in a Japanese garden is somewhat sacred and it is nice to have this notion over turned. Instead it is a good place to take a few drinks and something to eat, or even where the host might set up a bar for a party. It is all part and parcel of the evolution of a house and garden. As Ashizawa notes: “It was not until we had finished the project that we realised the Garden House seemed to complete the garden. Of course, a garden is never complete. I believe that it is constantly changing and evolving, but what this house has brought about is not just a mere space. It has a significant impact on the garden as a whole.”