In 2025, when artists self-describing as ‘interdisciplinary’ have become a cliché, it is perhaps difficult to appreciate the dominance of these narrow opinions and the authority they held until relatively recently.

Regardless, Sarah Robson forged her own direction and the in-betweenness of her work is one of its great strengths. The way that her work is at once sculpture and painting – operating both two- and three-dimensionally, where the painted surface is also an object – means that there is always a slipperiness in how we experience and read it. It is precisely this uncertainty, being made to question what we are seeing, that shifts us into a particular way of thinking where we understand that things might not always be as they seem.

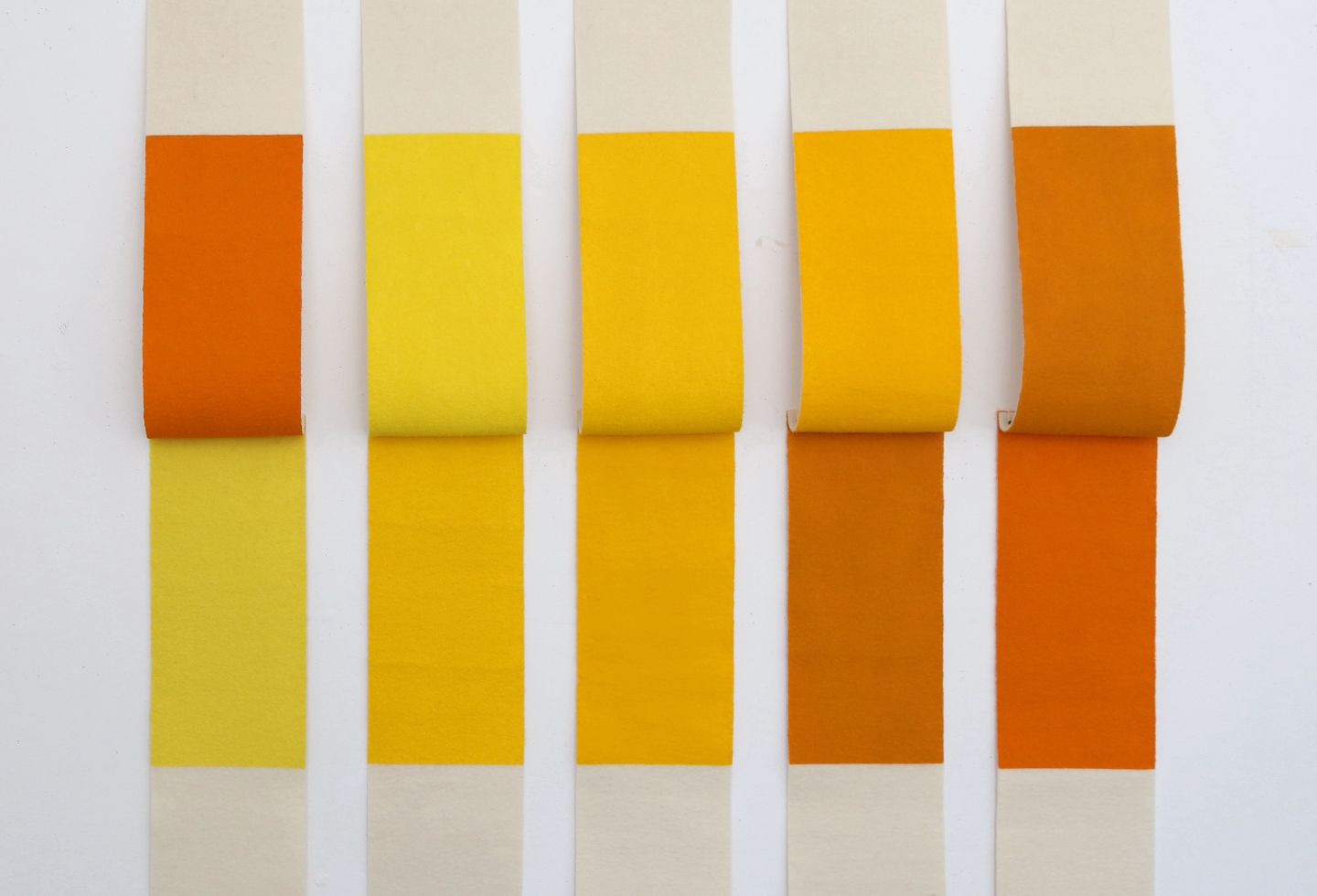

Robson has worked with a range of materials and modes since the early 1990s, including her work with architects to create sculptural interventions in private homes, commercial buildings and major public art commissions. Early on, she made abstract paintings that were measured and deliberate, but not so hard-edged as to obscure the hand of the artist. She pushes a singular idea through repetition – an approach that appropriately recurs in different ways throughout her practice. From the early 2000s, Robson made multiple series of hardwood wedges, including the cut-off edges of circles, curved on one side and flat on the other and pieces curved along both edges like crescents.

These smooth, often lustrous painting-sculptures were configured to form vertical and horizontal lines, or irregular, open circles; sometimes presented on the floor, other times wall-mounted, hovering. They feel like punctuation for architecture – parentheses that create an inside and an outside, that draw our attention to the scale and span of the space they occupy. The seriality of Robson’s works highlights small differences, honing our perception. As she reminds me, where art is visually minimal, there is space to swim around, to create our own connections and inferences.

When we meet, Robson hands me two small squares of dense, off-white industrial felt, partially painted oxblood red. I run my thumb between the painted and unpainted felt; from rigid and rough, to softer and more pliable. Wool felt is one of the oldest recorded textiles and Robson came to it when seeking a material more durable than paper, but that was organic and acted as both surface and support. She has been experimenting with what it can do both physically and conceptually since 2018.

Robson describes it as a “thirsty” material, absorbing liquid and paint as well as sound, physical impact and weather. It’s dense and even the 5mm-deep samples I thumb as we speak give a sense of how much this material can take into itself. It prompts thoughts about how experiences manifest in our bodies, becoming part of us. How the metaphysical becomes physical. And, how “felt” is also the past tense of the verb “feel”, making this absorptive material, poetically speaking, the sum of everything it experiences.

Related: Brahman Perera on Palinda Kannangara and Sri Lankan architecture

Robson’s felt works feel bodily. They are deep sighs; exhalations as a material curls, sags and sinks into a comfortable density. Works like In-between Stillness and Movement (2021) and Counter Curve (2022) appear effortlessly slung. But in reality, everything is deliberate. The forms are carefully calibrated and held in place with hidden stitches; their surfaces are fixed to slow further change. The works read as bodies or landscapes for the eye to travel across, to trace painted surfaces that give way to raw edges, to follow lines and loops that curve, coil, fold and come to rest.

Conversely, Corner Composition #5 (2009) is an array of white, square-section aluminium pipe that criss-crosses two perpendicular walls, turning a gallery corner into a kind of force field. The lines formed by the square pipe are all straight, but they are set at dramatic angles – like laser beams traversed by thieves in heist movies – creating a sense of intense force and movement. They break apart the clean space of the gallery.

White cube galleries are architecturally formulated to recede into the background so that the art can be at the fore. Robson wrangles a conversation with this architecture, forcing it out of its supposed neutrality, its conceit that art can exist in a vacuum – no context, no politics, no prosaic, messy necessities of everyday existence. It is easy to assume that the kind of art Robson makes – abstract, non-objective, or Concrete art – is doing the same thing. To assume that by seeking a kind of material simplicity and purity, this kind of art separates itself from the real world, existing in a realm that is pure aesthetics, sheer surface, all cerebral. But it is clear from Robson’s writing and from speaking with her, that this is not how her work functions.

Robson has written at length, particularly in her 2021 doctoral thesis, about how non-objective art constructs meaning and how this meaning is generated between the work, the viewer and the world. She has written about how art that is non-representational – that does not seek to reproduce imagery from the world – can elicit “complex, immaterial and philosophical questions about the nature of art and existence,” particularly around environmental issues and the climate crisis. Art that is illustrative and representational opens up the world to us by drawing expansive references, imagery and content into itself, allowing us to see relationships between elements that we would otherwise encounter spread apart in time and space. By contrast, reducing the palette of materials to singular, the colours to monochrome and the finishes to uniform, Robson focuses our attention and thinking. The lens is zoomed into an almost molecular specificity and we scan and re-scan to make sense of a form (is that line of thread hanging in space, or attached to the wall? Is its true shape the one I see when I stand in front of it or view it from the side?). In doing so, the mind slows down and visual and cognitive processes are sharpened. Art might not be able to actively effect change, but its affect might change us.

Robson’s works are like tools for thinking with, for attunement. Each person will respond differently to the same materials, colours and forms, bringing their own associations and memories: instead of bringing the world to us, these works invite us to bring the world to them. They are open metaphors, playing out fundamental tensions that we can apply to many questions, problems or memories. In part two of the 2003 Mellon Lectures at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, curator and art historian Kirk Varnedoe says: “By making simpler things, we don’t make things any simpler…reduction does not yield certainty, but something like its opposite, which is ambiguity and multivalence.” In abstract work like Robson’s, simplicity and reduction give rise to uncertainty and therefore to multiple and divergent experiences.

In her refusal to be didactic or specific, Robson creates space for open enquiry, curiosity and reflection. The more time you spend with her works, the more they give – but the catch is, they are not telling you more about them; they’re telling you about you.