Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany, in 1919 with a utopian vision: to conceive and design a new modern future. And while it has become synonymous with progressive, modernist design, Gropius established the school with a craft-based manifesto. He believed the fusion of art and craft would help stimulate social regeneration for Germany’s working classes. Like the Arts and Crafts Movement in the nineteenth century, Gropius’ design reform responded to the effects of industrialisation.

The Bauhaus emerged after a period of political, social and economic turmoil in Europe, in the aftermath of World War I, the German Revolution, Russian Revolution and months of civil war. Gropius and his avant-garde contemporaries wanted to positively impact society and translated their ideas and ideologies into the unity of all arts. Gropius’ vision unified architecture, sculpture and painting in a single creative expression.

The school offered a craft-based curriculum that would train artisans and designers capable of creating useful, beautiful objects for this modern way of living. A preliminary course included the study of materials, colour theory and formal relationships in preparation for specialised workshops in metalworking, woodworking, cabinetmaking, pottery, typography, wall painting and weaving (for the ladies – who were discouraged from participating in other areas).

Craft served as a primary source of inspiration during these early years, as embodied by Marcel Breuer and Gunta Stölzl’s African Chair (1921). Made with painted wood and colourful textile weave, the highly decorated chair is the earliest surviving piece of Bauhaus furniture.

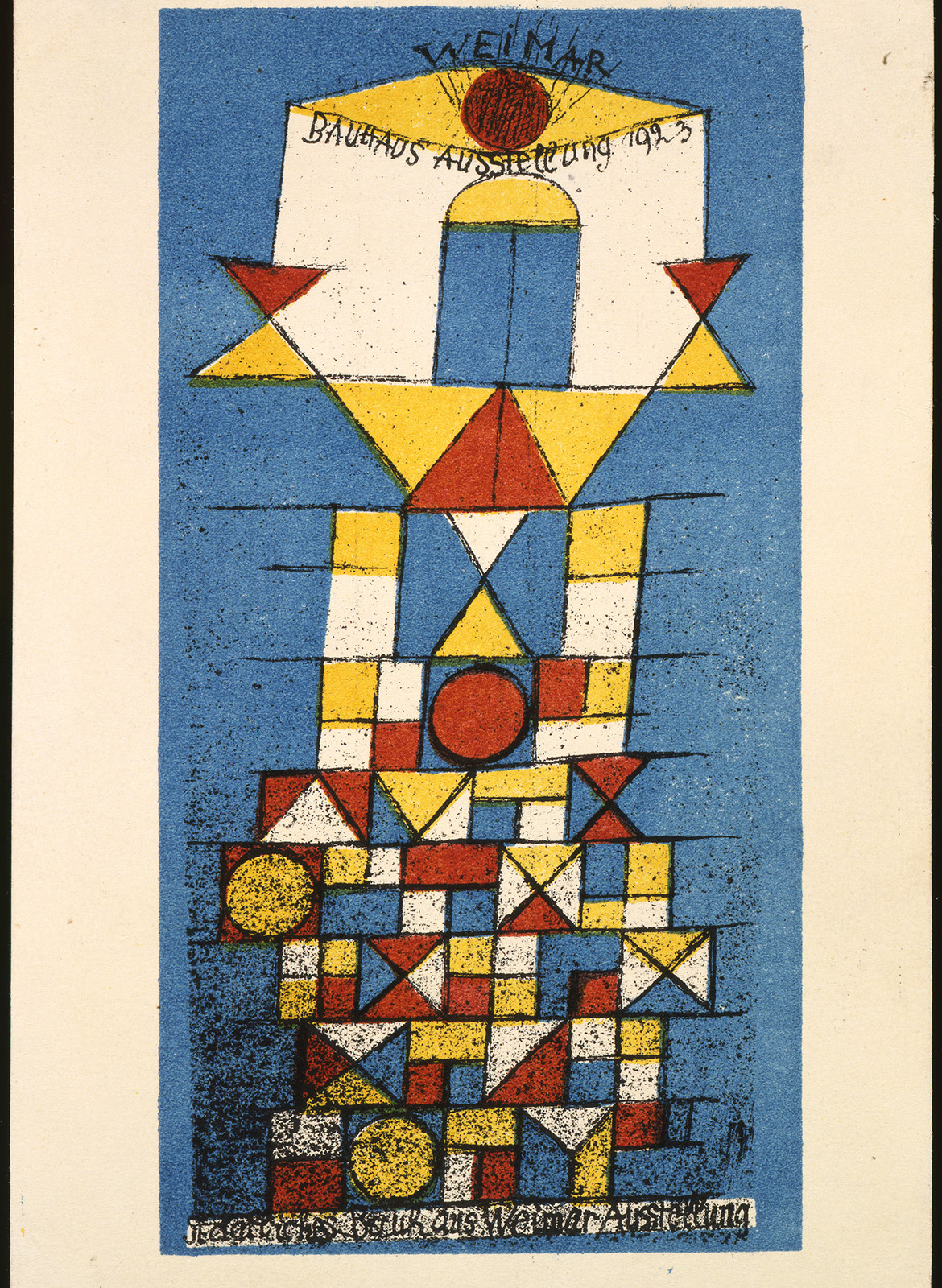

The goals of the Bauhaus shifted in 1923, moving away from the craft model to emphasise mass production. Reflected by its new slogan “Art and Technology – a new unity,” the Bauhaus embraced the power and potential of the machine and industrial technology. An abstract and universal design language emerged, freed from history, tradition and national identity. Designers remade the everyday according to the laws of function and efficiency. They distilled forms to their simplest elements and rejected ornament and decoration. Marianne Brandt’s Teapot (1924) is a quintessential expression of the Bauhaus aesthetic with its geometry of forms, honest construction and handcrafted production that looks machine made. (Brandt was the only woman working in the metal workshop.)

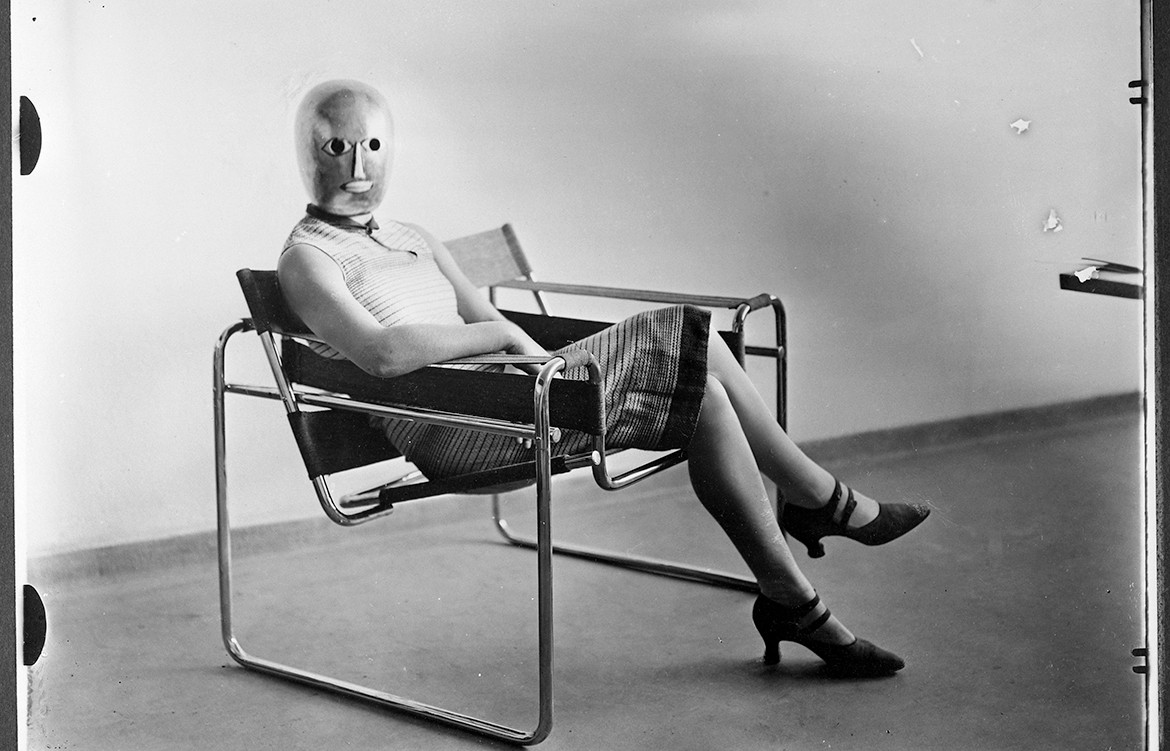

The cabinetmaking workshop, led by Marcel Breuer from 1924 to 1928, produced some of the most well-known and archetypal Bauhaus pieces, deconstructing conventional furniture forms to their essence, such as Breuer’s B3 Club Chair. The metal workshop developed prototypes for mass production, and the commercial success of the fabrics produced in the weaving workshop provided much-needed funds to keep the Bauhaus in operation. (Thank you, ladies!)

In 1925, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau where Gropius designed a new building that would become an exemplar for modernist architecture with its steel-frame construction and glass curtain wall.

Hannes Meyer succeeded Gropius as director in 1928. He stressed the importance of architecture and design for the public good but was replaced by Mies van der Rohe in 1930, pressured by the right-wing municipal government. The school moved to Berlin in 1930, and eventually shut its doors in 1933 due to the unstable financial condition of the school and the pressure of the Nazi regime. As Europe descended into war, many of the key Bauhaus figures emigrated to the United States, spreading their modernist approach to design underscored by a utopian vision.

Both an idea and institution, the Bauhaus propagated its ideology through products of design that have influenced generations of architects and designers around the world for 100 years and counting. Indeed, as Mies van der Rohe stated: “Only an idea has the power to spread so widely,”

Bauhaus Association 2019 is offering a program of events to celebrate the centenary. Under the motto “Reinventing the World,” the program explores the historical legacy of the Bauhaus as well as its significance for the present and future. The exhibition Original Bauhaus is on display from September 2019 until January 2020 at Berlinische Galerie, and the Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung building, which opened in 1979, is being extended with the addition of a new museum.

Bauhaus

bauhause-dessau.de

We think you might also like A Reference Point For When East Met West