Some projects just speak to one another. Among the 26 shortlisted projects for this year’s Habitus House of the Year, supported by Winnings as well as Billi and Rogerseller, there are two New South Wales houses that offer a compelling dialogue about the state of housing in Australia in 2025. Indeed, they were the last two standing during the jury debates held at Winnings Richmond and has each duly won a major award.

First, Clifton House by Anthony Gill Architects is your 2025 Habitus House of the Year. It’s in Bondi, a famous area in Sydney, and it deals with questions of density, privacy, overlooking and natural light.

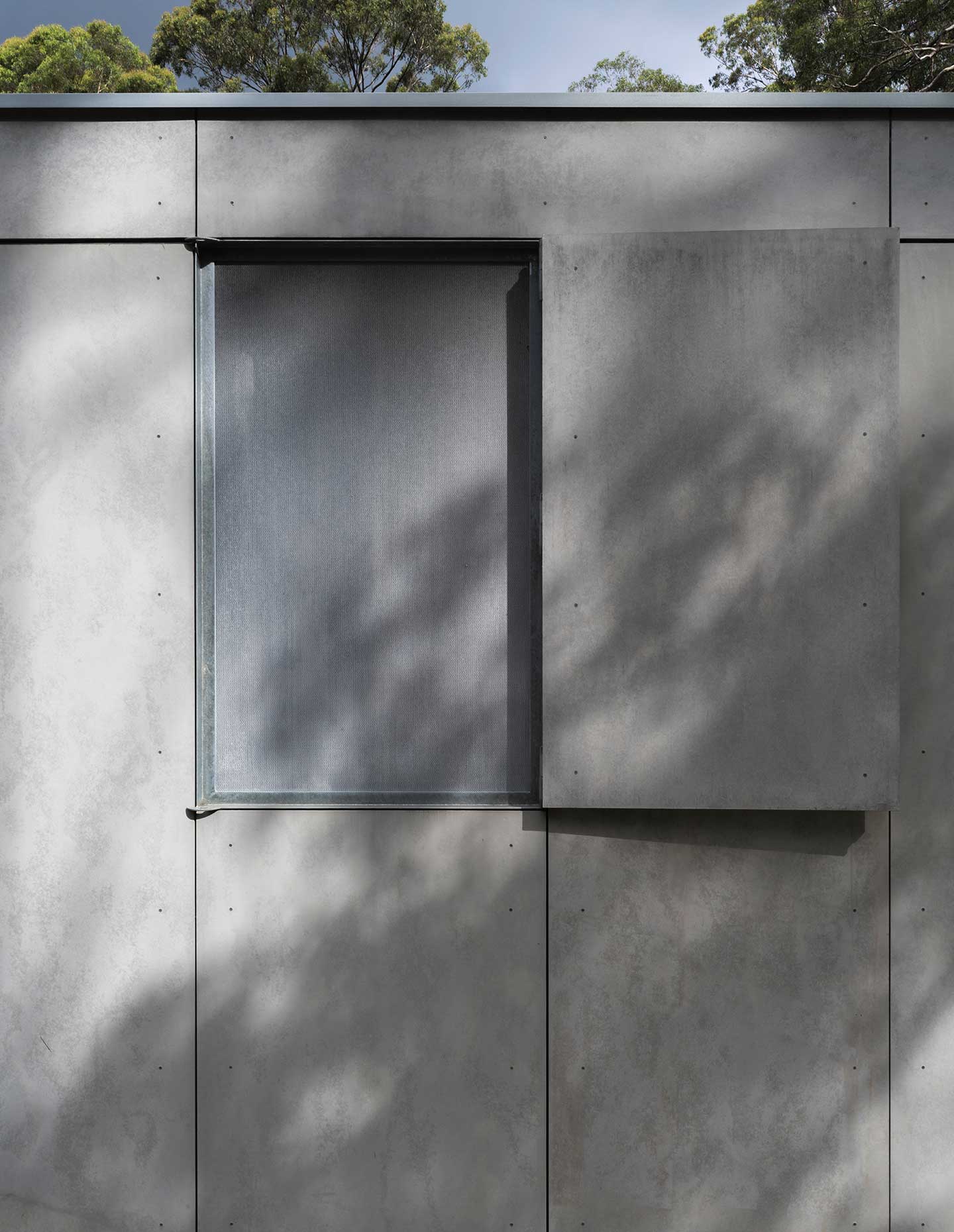

Second, Amongst the Eucalypts by Jason Gibney Design Workshop (JGDW) has taken out the Editor’s Choice Award. Located several hours up the coast by Seal Rocks, it engages with the regional coastal landscape, wildlife and bushfires.

On the surface, then, not much in common. However, during our roundtable discussion for STORIESINDESIGN podcast at The Commons in Sydney, what became clear is that the two projects not only address conceptually similar issues but do so in strikingly similar architectural terms. The principles underpinning both projects are highly similar, even if they find very different manifestations.

Both Gibney and Gill (below, left and right respectively) spoke about surroundings, for one. With Amongst the Eucalypts, that primarily concerns the casuarina forest and native wildlife at the site. Clifton House might be more concerned with the possibility of overlooking neighbours, but both projects are fundamentally attuned to the life that immediately surrounds them.

Related: This year’s contenders for the Winnings Emerging Talent Award

“I’ve always thought privacy is slightly overrated,” says Gill. “Clients are always talking about privacy as their greatest concern, and there are certain areas where you really need it. But at other times, connections to the street [and] to community are super important. So, it’s about getting that balance right by solving it in certain areas and giving the clients comfort that they’re going to be able to inhabit it the way they want.”

Each project also places a significant emphasis on landscape design, albeit at different scales. Gill has taken great care to curate interstitial moments of greenery behind fibreglass surfaces, while Gibney deliberately sets the house up in the trees as well as crafting private planted areas.

“We needed to come up with something quite different in terms of what council would accept,” explains Gill. Something, he continues, that “would provide privacy, but would also give us an opportunity to make those spaces upstairs really rich and enjoyable to inhabit. We planted these roof gardens and used this off-the-shelf fiberglass, corrugated material – which is probably more at home in industrial use. But it creates this beautiful soft light, and the gardens grow feverishly underneath these screens. By the time you get upstairs, it actually has this otherworldly character to that does make you forget that you’re in Bondi.”

Describing his own engagement with the landscape by Seal Rocks, Gibney says: “As you go up the hill, you lose sight of the lake. But then as you go higher and higher, it appears again – and now, it appears beyond the canopy of the trees. So, you’re halfway up the hill and you have a mature tree canopy below your eyeline, with water above. Everything changed when we got up there… You were in this undeveloped area where nobody built houses, and so even the fauna – the birds and the lizards – just seem so at home. They weren’t bothered because they weren’t used to people being there when we were building.”

Like all good architecture, it’s about context – and it’s about not taking the similarities literally. With both architects in agreement, Gibney concludes: “These are buildings in an Australian suburban area or an Australian bushland site, and we do have unique climatic conditions that draw out a certain response. And yet at the same time, I think you could take the same logic or principles and apply them anywhere – because [the parts] that became the solution to deal with those parameters are about bringing back the humanity and the nature side of how we live and dwell anyway.”

Listen to the full episode here!